Thinking in numbers

Painting cycle, archival exploration, collage and text

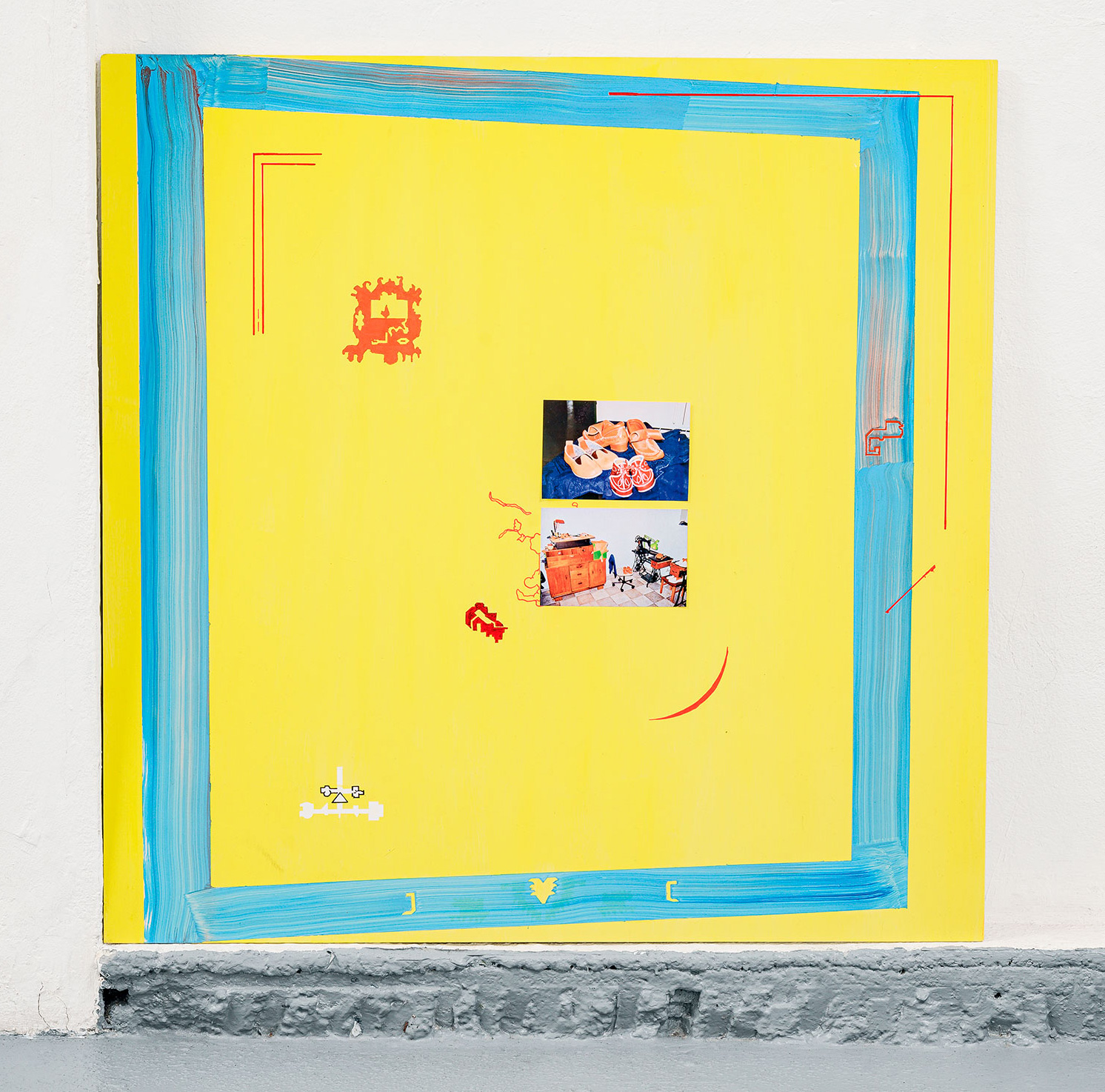

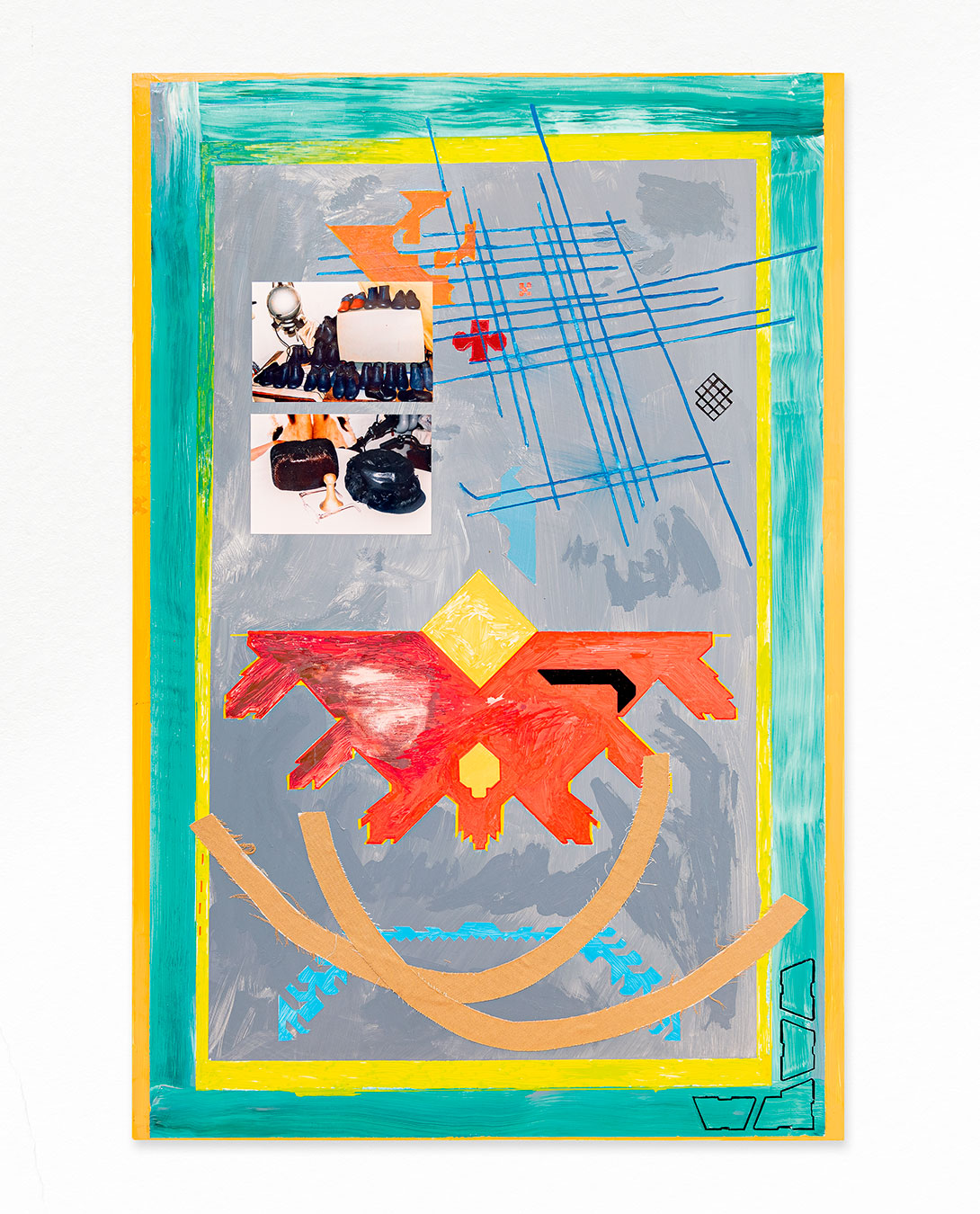

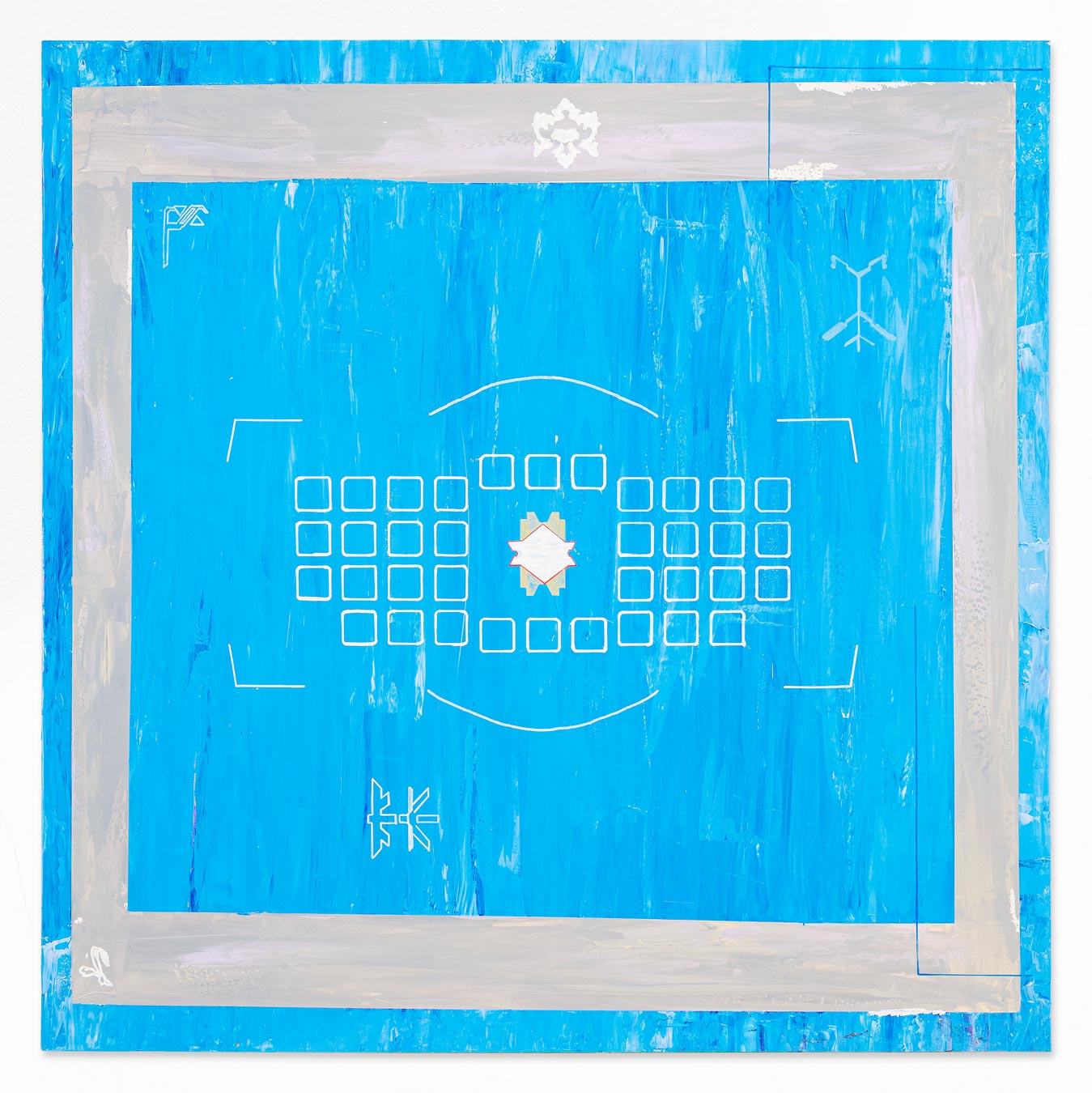

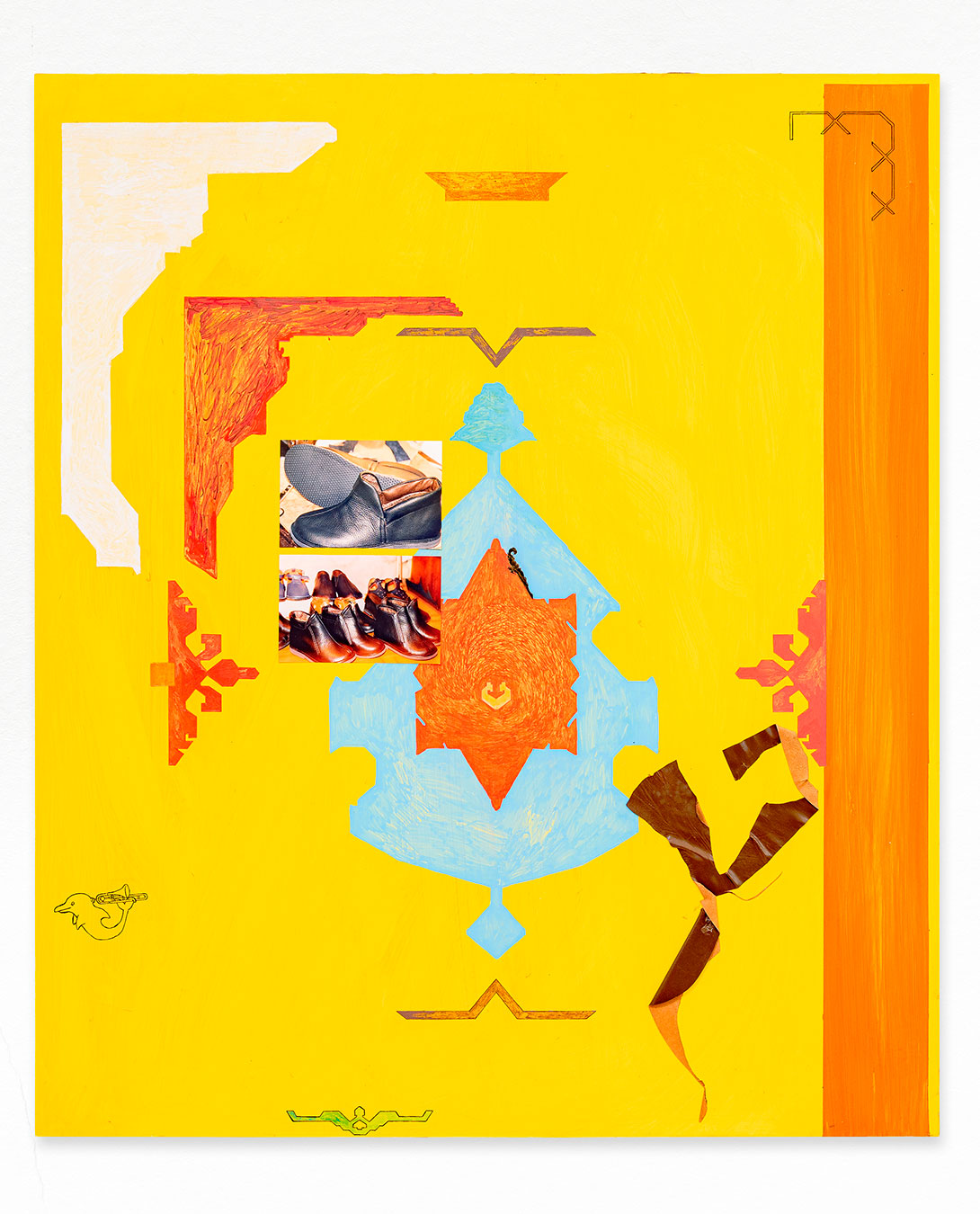

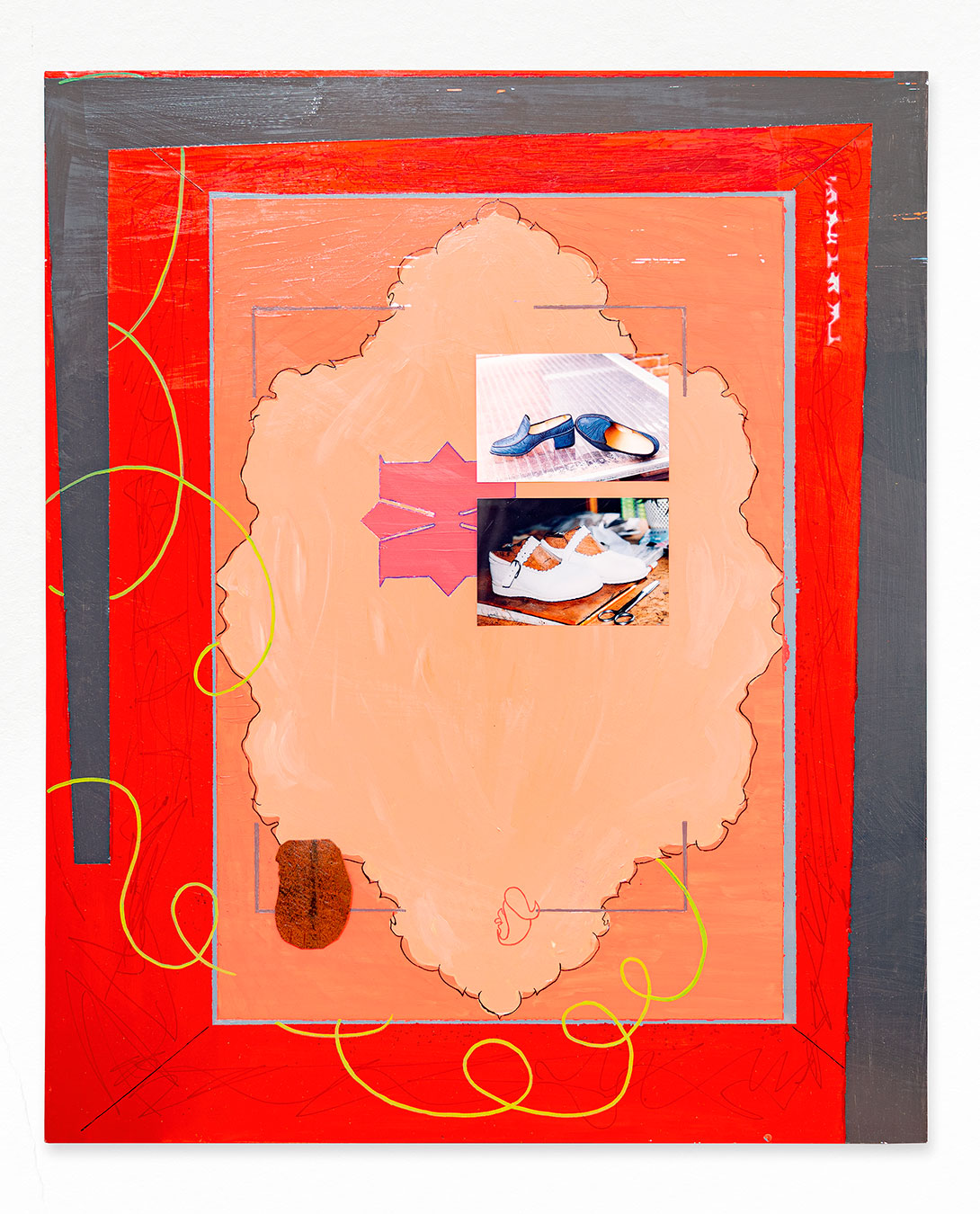

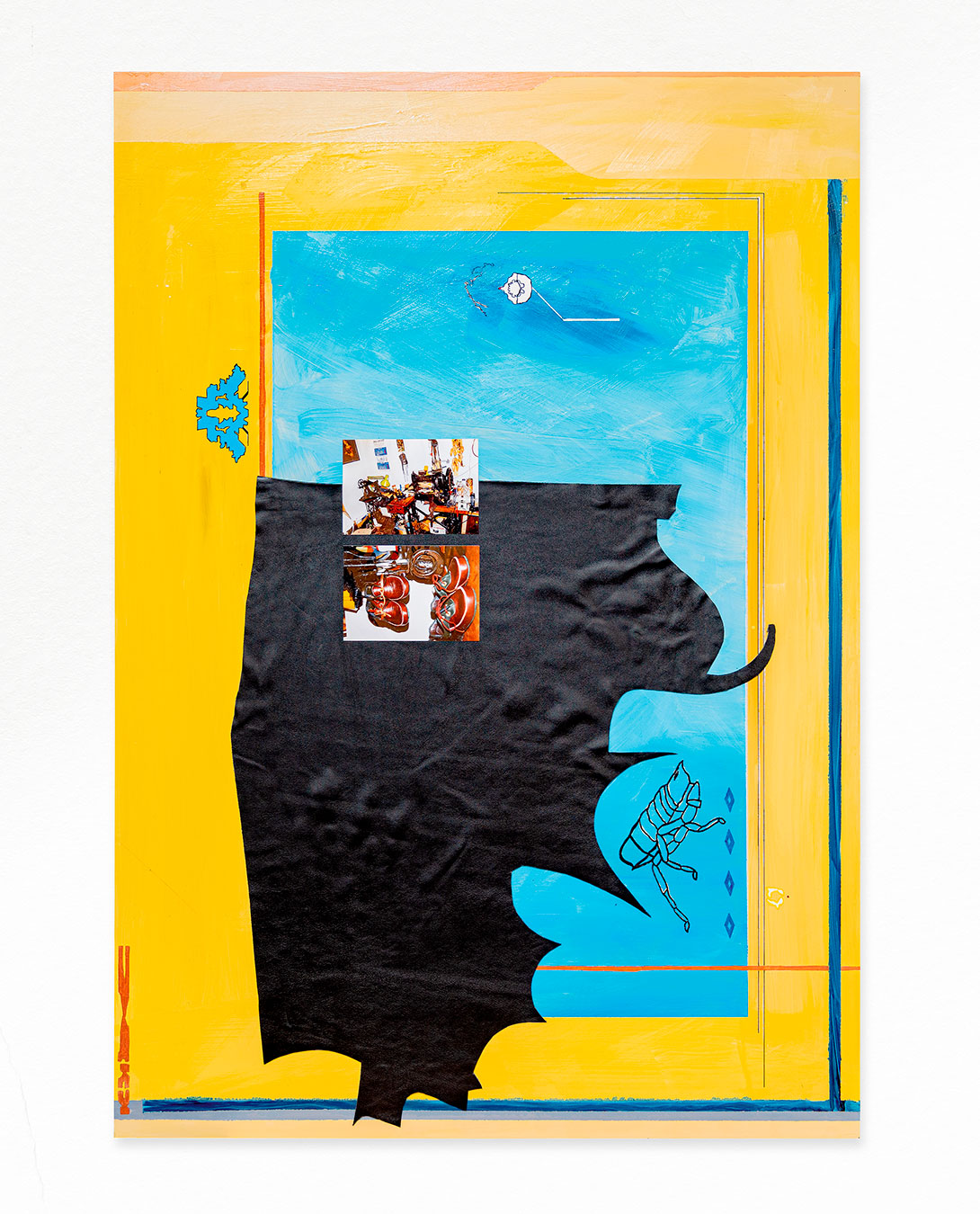

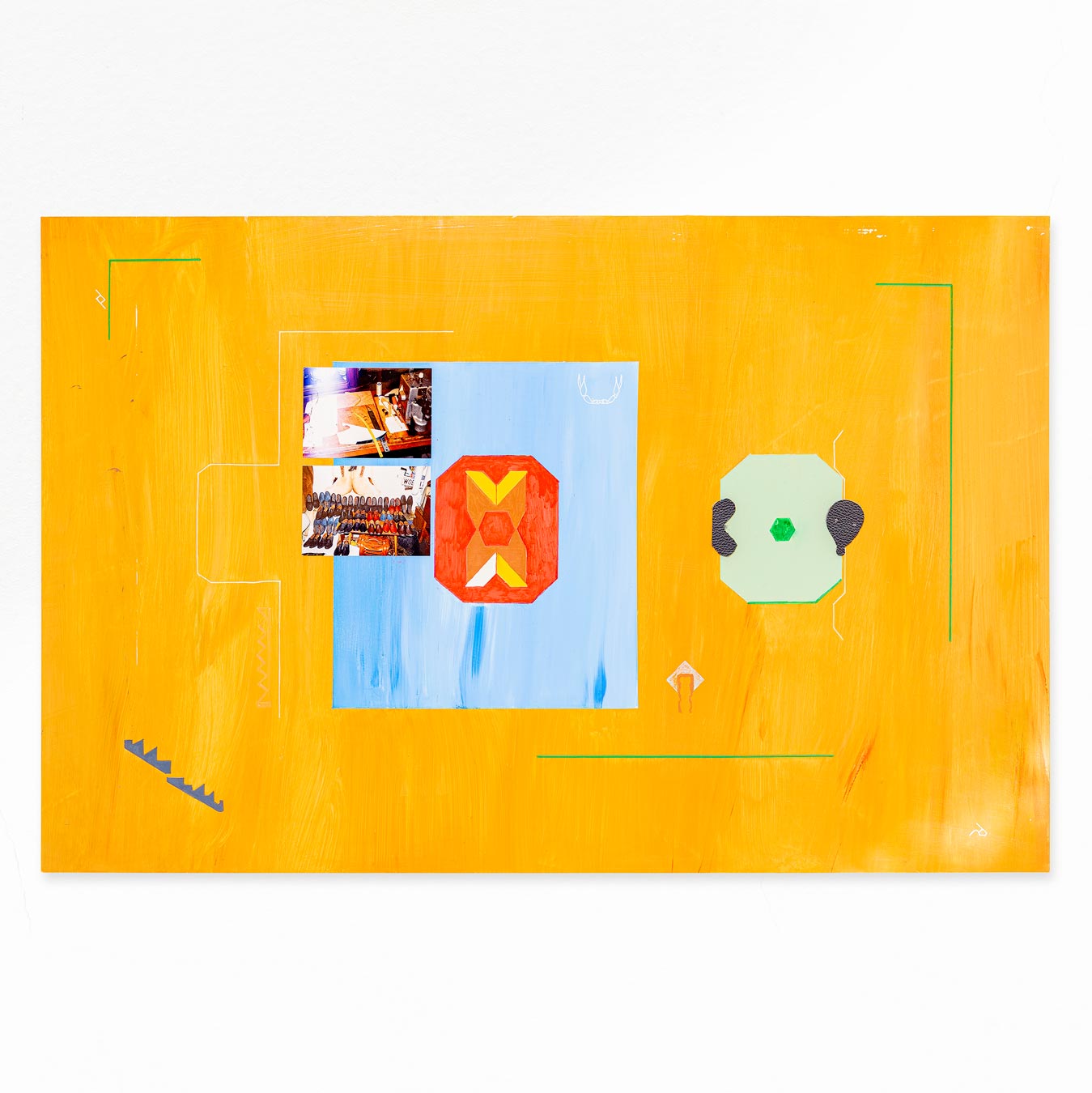

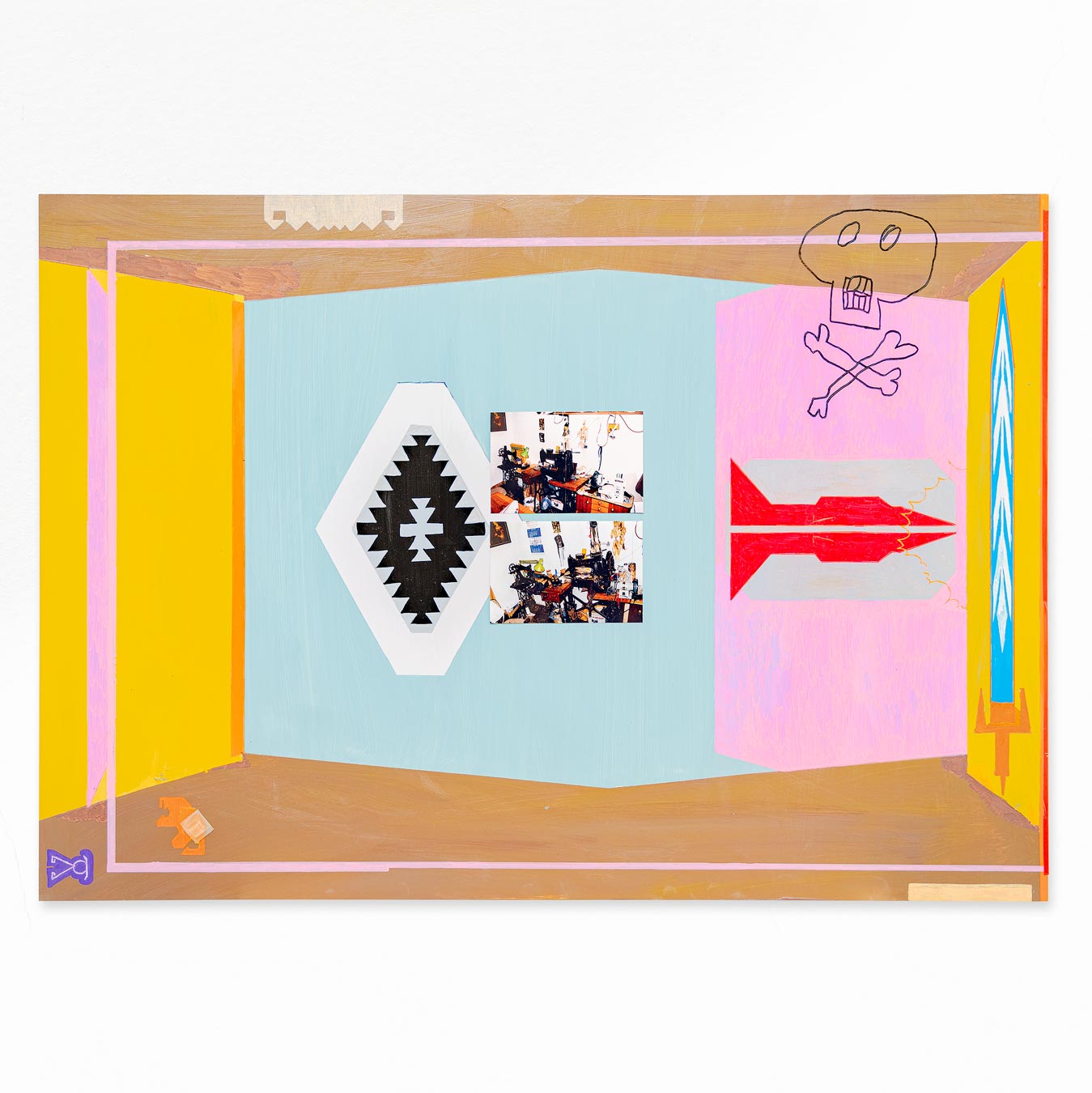

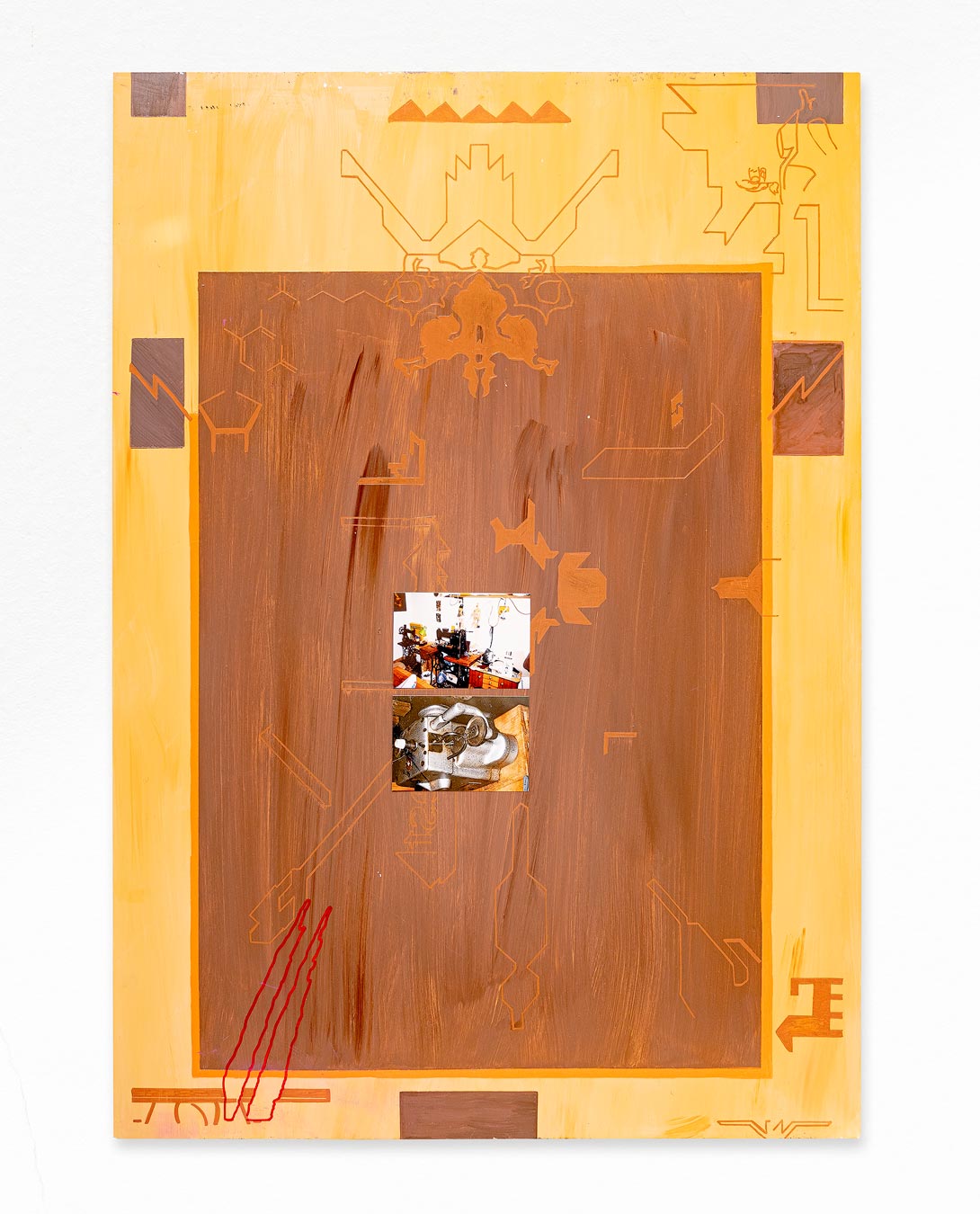

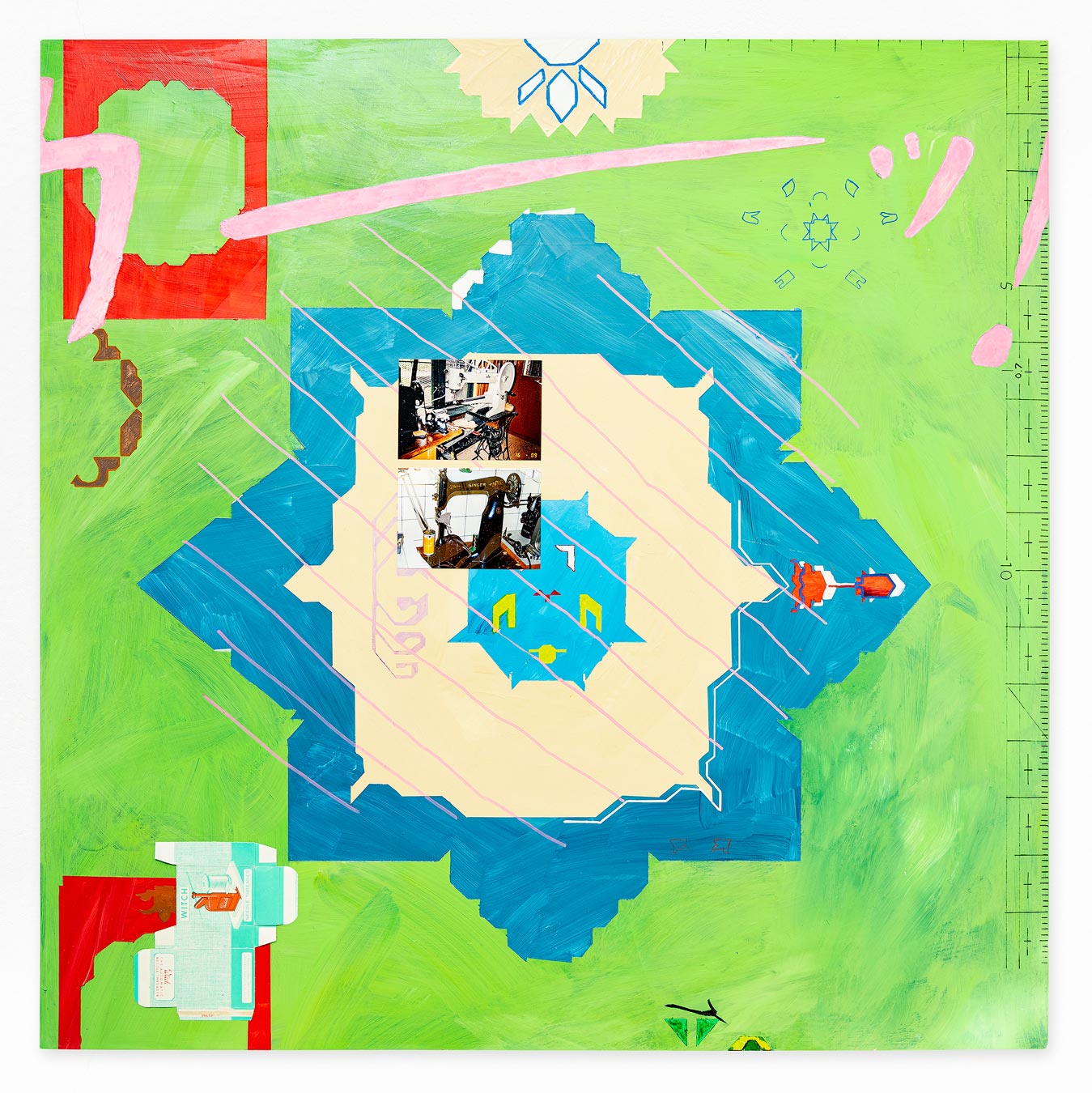

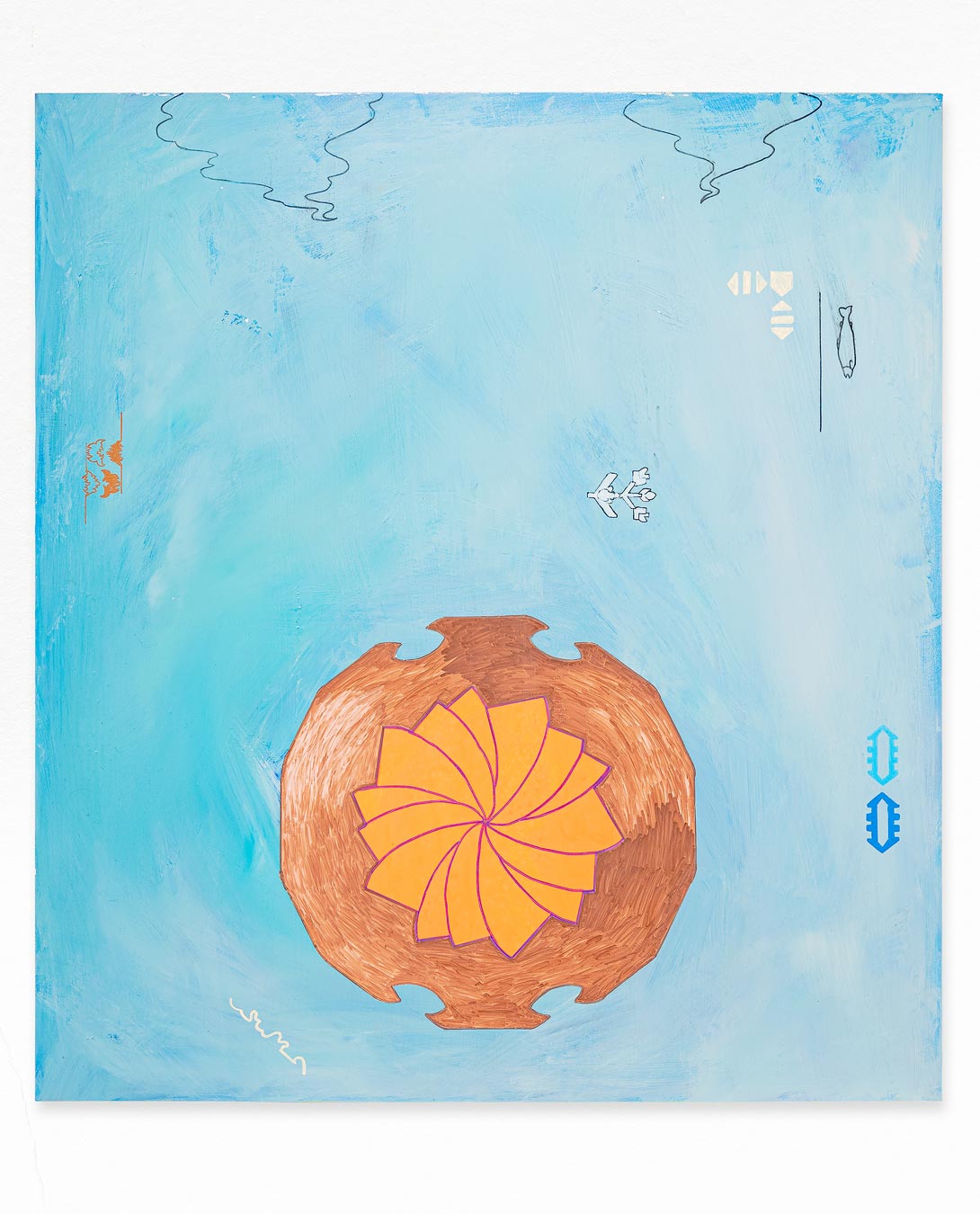

‚Thinking in Numbers‘ is inspired by my late grandfather’s collection of around 300 photographs of shoes. These images, taken by my grandfather, a cobbler, before selling the shoes, have a distinct and unusual aesthetic reminiscent of a dilettant version of the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher.

For my project, I create collages by attaching photographs and other objects from my grandfather’s workshop onto rigid foam boards that I paint with acrylic and markers. These collages combine elements of Eastern European carpet design with freehand drawings and also incorporate Rohrschach and anime elements. I also include leather scraps that my grandfather used before he stopped building shoes. Upon closer inspection, these scraps reveal the outlines of the shoes.

I have structured these collages into multiple chapters. To further this concept of chapters, I have also attached two short stories to the rigid foam boards alongside the other materials. These stories are based on my grandfather’s life and anecdotes from my family history.

The work has been kindly supported by Stiftung Kunstfonds and twice by Hessische Kulturstiftung.

‚Thinking in Numbers‘ is inspired by my late grandfather’s collection of around 300 photographs of shoes. These images, taken by my grandfather, a cobbler, before selling the shoes, have a distinct and unusual aesthetic reminiscent of a dilettant version of the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher.

For my project, I create collages by attaching photographs and other objects from my grandfather’s workshop onto rigid foam boards that I paint with acrylic and markers. These collages combine elements of Eastern European carpet design with freehand drawings and also incorporate Rohrschach and anime elements. I also include leather scraps that my grandfather used before he stopped building shoes. Upon closer inspection, these scraps reveal the outlines of the shoes.

I have structured these collages into multiple chapters. To further this concept of chapters, I have also attached two short stories to the rigid foam boards alongside the other materials. These stories are based on my grandfather’s life and anecdotes from my family history.

The work has been kindly supported by Stiftung Kunstfonds and twice by Hessische Kulturstiftung.

“In a certain town there lived a cobbler, Martin Avdéitch by name. He had a tiny room in a basement whose one window looked out onto the street. Through it one could only see the feet of those who passed by, but Martin recognised the people by their boots. He had lived long in the place and had many acquaintances. There was hardly a pair of boots in the neighbourhood that had not been once or twice through his hands, so he often saw his own handiwork through the window.”

from Martin the Shoemaker by Lew Nikolajevich Tolstoi

A pile of photographs. An archive. Calling, asking to be seen, read, remembered, interpreted. Provoking curiosity, fascination, fetishisation. Even though the images are silent, a voice – a brush, a pen, pieces of leather, torn fabric – attaches itself to the photographs, drawing new lines that extend from their frame, becoming fibres weaved into a tapestry of imagined narratives, private and common. A gesture of stepping back, an expansion of the frame, as the photographer, the shoemaker, becomes the last.

The shoemaker takes photos of the shoes he makes. A pair of shoes and nothing more. And yet he holds a boot in his hand. He lays a pair of shoes next to others on the working table or places them against a DIY background, highlighting colours, patterns, and other special features. After being crafted by the shoemaker from the positive last, the foot-like wooden mould around which the shoe takes its form, each shoe is (re-)framed by him, captured on the camera’s negative, retrieved from the world of usage and work and into the world of images. Unworn, before time had the chance to remould them.

Each of these photographs was taken, kept, and shown for a reason. Developed from the negative, turned positive again. Meant to be retained, stored, and respectively shown in private or public, within the family circle or in the community. These images could have multiple uses or be put to contradictory use, but when the shoemaker stares down at the photographs, his faint reflection flickers on the glossy coating.

· Ben Livne Weitzman

Summer time calls for summer work.

In Lüksemburgi this meant tending to the wine.

As a resident of the Caucasus young Oscarovich was, of course, familiar with such tasks. He was jumping at the thought of being able to help and jumping even more to taste the sweet fruit. His mother, Hilde Heinrichova, who is not to be confused with young Oscarovichs later wife, Hilda Jakobova, tasked him to bring a clay pot to her father, young Oscarovichs grandfather Heinrich. This clay pot contained what so many field hands were thirsting for the most during their hard toils on the fields: wine mixed with water.

So young Oscarovich was sent to Heinrich. The way was not far as it simply meant a short trip up a hill. Driven by duty and vigor Oscarovich was sure not to fail. Only to do so at the first sight of his grandfather. As he screamed full of joy “дедушка, дедушка!” he watched in horror as the pot of clay containing the water mixed with wine slipped from his hands and fell onto the ground and into pieces.

Terror grabbed him and he began to cry. Heinrich observed the scene from afar and coming to help he sat the boy unto his lap. But the boys grief could not be stopped nor soothed nor calmed. Looking into young Oscarovich eyes, he said: “Look upon me, for the pot is no longer broken.”

And in front of them the pot came to be. Young Oscarovich would not believe his eyes as his grandfather had accomplished this feat, this magick, directly in front of him. Heinrich only knowingly nodded. A man of medicine and suggestion and fast pot repair he willed the recompletion of the pot into existence. The locals considered him changed after his time spent in Vienna, where he gained his approbation, and during which he was rumored to have spent time with a man named Freud and other members of the occult. People were talking about Heinrichs own cabinet in Lüksemburgi and the screams they said they would hear. For young Oscarovich only awe was left on that day as he became a witness to such powers as he skirted back to his mother.

Years later, as a man, he remembered sneaking into Heinrichs private cabinet. Books of black and white magic lined the sides but most prominent was a carton of surgical instruments standing on a table. In it lay a fine scalpel. More of a lazaret than an occult chamber young Oscarovich concluded later that Heinrich mostly had helped the locals in all their pains. It was a sad room whose owner ended up having an even sadder story. As someone else would later write: “It was a room which if dwelled upon could make you end up full of strange, diffuse compassions and which would lead you to believe that it might be a good idea to wipe out the whole human race and start again with amoebas.”

Photography has always been an act of supression: the first photo of a person did not show the cobbler but his patron it sure did.

Four years before Oppenheimers atom bomb would lighten up the sky young Oscarovich found himself on a traincart. He and his family were participating in a process known as deportation. It was 1941. A german dictator with a loud voice and even louder mustache decided that he had enough of the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union in turn decided it had enough of a hundred thousand Caucasus Germans. So every one of them had to leave. Everyone who was not married to a georgian.

It was a time in which humanity engaged in its favorite pastime: oppressing the other. The Caucasus Germans found themselves on a ferry in the Caspian sea hailing from Baku. But where that ferry was going even the ferrymen did not know. As someone else would later write:

“For two months ethnic Germans from the Caucasus were pointlessly dragged back and forth on the Caspian Sea, and more people, especially children, were dying of starvation. They were just thrown overboard. My four-year-old son was thrown there as well. My other son, seven years of age, saw that. He grabbed my skirt and begged me with tears in his eyes: ‚Mummy, don’t let them throw me in the water. I beg you, leave me alive, and I will always be with you and take care of you when I grow up’… I always cry when I remember that he also died of starvation and was thrown overboard, which he feared so much.”

Heinrich, young Oscarovichs grandfather, was not there to witness this. Four years before this he vanished. In the 1950s Christine Josefova, Heinrichs wife, would find out about her husbands fate in a letter by the esteemed party commitee. The letter announced to her the commitees decision to rehabilitate Heinrich as well as his medical approbation.

In the same letter the commitee also regretted to inform her of Heinrichs passing. Unfortunately he had won the first prize in a political joke contest on the occasion of Lenin’s 1942 birthday in the prison of Tiflis. The nature of the prizes was as follows: the third prize granted the lucky winner three years of labor camp in honor of Lenin, the second prize extended the third prize to seven years in honor of Lenin, while the elusive first prize granted you a personal meeting with the man himself.